The enigmatic Irish-born architect and designer Eileen Gray tiptoes a curious historical line between obscurity and cult legend, all depending on whom you ask.

On the one hand, she has been called the “Mother of Modernity,” a name given to her by Cloé Pitiot, a leading scholar of Gray’s life and work and the curator of “Eileen Gray: Crossing Borders,” which recently opened at the Bard Graduate Center Gallery.

Gray lives up to the lofty sobriquet in ways few others could. As one of just a handful of women who practiced architecture professionally before World War II, and as a part of the Modernist architectural movement, she stood toe-to-toe with the likes of Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe, and Walter Gropius.

And though she is often compared to designers Charlotte Perriand and Ray Eames, their careers took off decades after Gray’s had flourished, as Nina Stritzler-Levine, director of Bard Graduate Center Gallery, is quick to point out.

Eileen Gray, Drawing for Boudoir de Monte Carlo (1923). Courtesy of Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris. Photography by Christophe Dellière.

Yet despite her singular legacy, Gray has remained surprisingly unknown outside niche architecture and design circles.

The Bard exhibition, then, is a long-overdue look at one of Modernism’s great talents. It is the first show devoted to Gray in the United States since the Museum of Modern Art’s “Eileen Gray, Designer” was held 40 years ago, in 1980.

The current show presents the striking diversity of her abilities through 200 pieces of furniture, architectural drawings and models, and textiles, some of which have never been shown before.

Pitiot, who curated the seminal exhibition “Eileen Gray” at the Centre Pompidou in 2013 (it traveled to the Irish Museum of Modern Art in Dublin in 2014), presents seven years’ worth of new research in the new show. And that research, assembled with the help of curator Jennifer Goff of the National Museum of Ireland and Stritzler-Levine, has been assembled through a Herculean effort.

That’s because Gray didn’t believe in preserving her papers; in fact, she destroyed much of her own correspondence and materials because “she wanted her private life to remain private,” Pitiot said.

Eileen Gray, Lacquered Wood Screen ( 1921–23). Courtesy of Kelly Gallery and Stephen Kelly, New York.

Many of the show’s new discoveries emerged from hours spent digging through the archives of her friends and contemporaries, including Auguste Rodin, fashion designer Jacques Doucet, dancer Loïe Fuller, and occultist Aleister Crowley.

What emerges is a picture of a multi-hyphenate and daring talent—and a woman who was intentionally elusive and fearless, but nevertheless subject to the biases of her day.

Born in 1878 to an upper-class family, Gray studied at the Slade School of Design in London before moving to Paris to study at the Académie Julian. An early, rare drawing of a nude female figure in the show speaks to her artistic training, and to the fact that her understanding of the structure of the body informed her highly specified approach to furniture.

She soon met the artist Seizo Sugawara, with whom she would study the art of traditional Japanese lacquerware, and later, after establishing a weaving workshop with her friend Evelyn Wyld that employed up to eight women at a time, she would operate the Galerie Jean Désert, a Parisian purveyor of Modernist interior decor, from 1921 to 1930. There, she also showed examples of Modern art, making her an early woman gallerist, too.

Eileen Gray, Rug ( 1922-24). Courtesy of Galerie Jacques De Vos.

Gray often included riddles in her designs and titles, and her store’s name is evidence of that: Jean Désert is in part a tribute to her lover, the Roman architect Jean Badovici, as well as to the terrains of North Africa, which she adored.

But the name is also an aptly employed male pseudonym that allowed Gray to navigate her proprietorship with disguised ease, a detail that reveals how Gray operated. “When people would come into the shop asking for Jean Désert, she would say he wasn’t in today,” Pitiot remarked.

When she turned to architecture with the encouragement of Badovici, she brought to it her unique sensuality, which prized the individual. “She created a very human architecture,” Pitiot said. “Even if the design is the same, there are differences.”

Pitiot points to two seemingly identical chairs with a slight difference: one has squared legs and the other’s are rounded. Other designs included her Fauteuil Non Conformist chair, with one raised arm, for smoking, and one sloped arm to allow for easy turning while chatting.

Eileen Gray, Dining room serving table (1926-29). Courtesy of Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne. The table has a disguised back set of drawers for valuables.

Her designs were defined by their specificity, but also by their multi-functionality and Gray’s awareness of the preciousness of space. One of her works is a rounded serving cabinet (better to bump into a soft edge than a sharp one) with a disguised set of drawers at its back, for keeping valuables; another is a camping tent with a built-in bed and dining table.

This lyricism won her enthusiasm—she designed for the Maharaja of Indore, celebrated courtier Jacques Doucet, and famed milliner Juliette Lévy—but it also inspired jealousy.

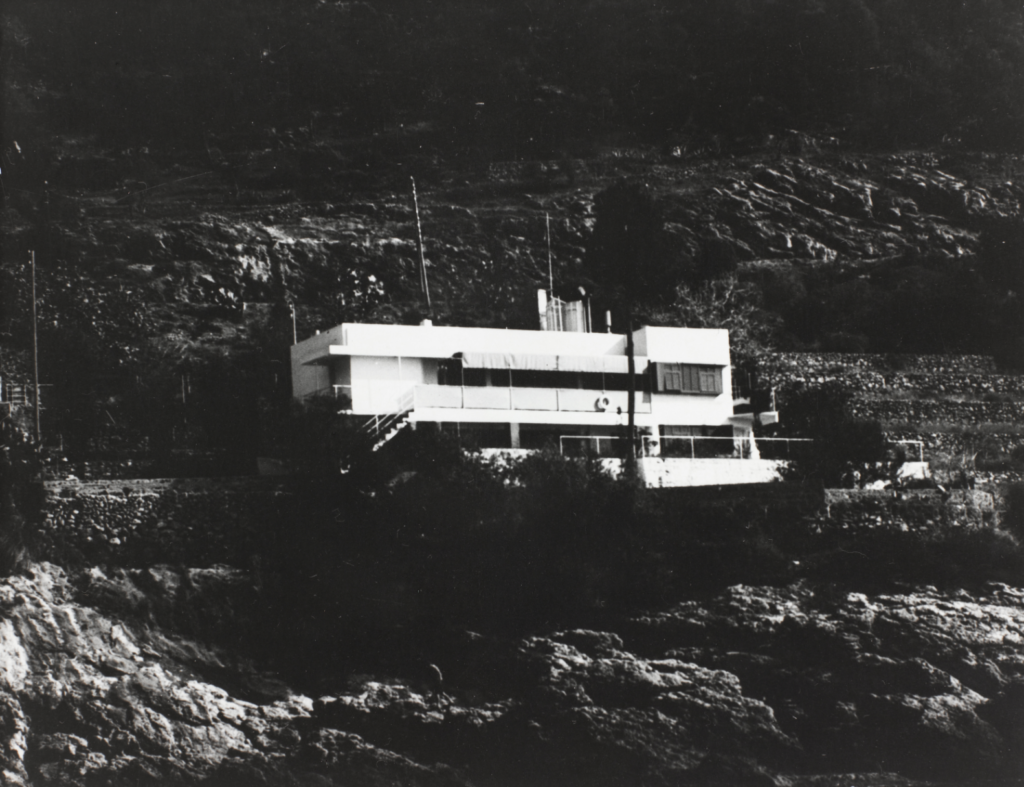

Her masterpiece first architectural project, E1027 (1926–29), a pristine white villa on the Southern coast of France designed as a seaside abode for a couple, so obsessed Le Corbusier that he situated himself upon it quite literally, building up the land surrounding it with his own brightly colored edifices.

When Gray moved away from the villa after a split from Badovici, Corbusier infamously painted the bare walls of the building with riotously colored frescoes, despite the fact that Gray had explicitly designed them to be bare. (To make matters worst, Le Corbusier painted them in the nude).

View of the south façade of E 1027 from the sea, Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, unknown date. Courtesy of the Centre Pompidou, Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Paris, and Fond Eileen Gray.

“By the time architectural interest emerged in E1027, Badovici and Corbusier had seemingly written [Gray] out of her own project,” Goff, the National Museum of Ireland curator, said.

Yet despite the insult, Gray carried on, seemingly undeterred, and designed Tempe à Pailla (the second of her three homes), a retreat in the French hills in which she synthesized her living and work spaces into complete harmony.

At the time, she was 54 years old. (She would live until 1976, when she died at age 98.)

“What is remarkable about Gray is that she was underestimated, but never looked back,” Strizler-Levine said. “She just kept moving forward.”

“In her 80s, she was considering whether or not to get a motorcycle,” Strizler-Levine said. “She had so much spirit, and no fear.”

Source: Exhibition - news.artnet.com