Female artists’ contributions to the Surrealist movement may be well known, but only a handful have received the recognition they deserve. A scholarly new exhibition in Frankfurt has brought together works by 34 important artists, several of whom have been long overlooked and excluded from the male-dominated art historical canon.

The quantity and diversity of their work shows how a female perspective was central to Surrealism from its birth in the aftermath of World War I. Included in “Fantastic Women. Surreal Worlds from Meret Oppenheim to Frida Kahlo” at the Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt in Germany are a staggering 260 paintings, works on paper, sculptures, photographs, and films, some rarely seen before.

On show are works by lesser known artists, such as the Toyen, Bridget Tichnor, Alice Rahon, Kay Sage, and Ithell Colquhoun, alongside their more famous contemporaries, Frida Kahlo, Meret Oppenheim, Lee Miller, Claude Cahun, Leonora Carrington, Dora Maar, and Dorothea Tanning. Highlights include a screening of pioneer French filmmaker Germaine Dulac’s . Made in 1927, it is considered to be the first Surrealist work in the history of film.

“To this day, the names and works of the huge number of important women artists throughout the world are missing in many reference guides and survey exhibitions on Surrealism,” writes the exhibition’s curator, Ingrid Pfeiffer, in the publication that accompanies the show. “The reasons for this are many, including the endless repetition of an outdated canon in spite of recent research—a problem which pertains to art history in general.”

Many of the artists are connected through their association with Surrealist co-founder André Breton, or through their participation or contributions to key group exhibitions, and publications. The exhibition also explores the network of friendships of these female pioneers that stretched from Europe, to the US, and Mexico.

Dorothea Tanning, (1942). Collection Ulla und Heiner Pietzsch, Berlin. © The Estate of Dorothea Tanning/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020. Photo: Jochen Littkemann, Berlin

In 1944, Breton, the high priest of Surrealism wrote: “It is high time for woman’s ideas to prevail over man’s, whose bankruptcy is clear enough in the tumult of today. It is up to the artist, in particular, to privilege as much as possible the feminine system in opposite to the masculine system, to draw exclusively on woman’s faculties.” The exhibition notes that he was supported, including financially, by several key women in the movement, including the French artist Valentine Hugo.

Leonor Fini, (1946). © Weinstein Gallery,

San Francisco and Francis Naumann Gallery, New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020

The show charts many important Surrealist themes, such as the “exquisite corpse,” collaborative artworks, automatic writings, and depictions of mythical creatures, and landscapes of the subconscious. “On the whole, the [Surrealist] movement in many ways strikes as decidedly ‘feminine’, since it rejected all traditionally masculine, patriarchal, and imperialist structures,” notes Pfeiffer. The female Surrealists had to deal with their share of sexist attitudes but they experienced a lot of freedom for the time, and were never mere muses.

Among the highlights of the exhibition is a trove of self-portraits, a genre that female Surrealists made their own; it was a form much less used by their male counterparts. Pfeiffer speculates why this was the case, writing: [M]any of them had been portrayed before by their male fellow artists as an ‘object’ of male projection.”

Meret Oppenheim, (1933). © Kunstmuseum Solothurn / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020

She cites Meret Oppenheim standing nude beside a printing press in Man Ray’s famous series, or Unica Zürn depicted as a tied-up doll in a work by Hans Bellmer. Women, according to Pfeiffer, were “in many cases, anonymised as ‘the woman,’ a mysterious, desired being. The omnipresence of the female body in Surrealist art confronted women artists with the task of growing, with their own ways of seeing and thinking, from a passive object into an acting subject.”

The exhibition includes the work of the late Surrealist Louise Bourgeois. By the end of the end of the 1960s, many of the pioneering female artists of the movement were living in relative obscurity, their Surrealist art only gradually rediscovered shortly before they died, or posthumously. “Fantastic Women,” which travels after its run in Frankfurt to the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Denmark, reveals how the art movement was shaped by many more female artists than historians have hitherto recognized. They were extraordinary women whose often playful and self-confident approach to their body image and female sexuality was ahead of its time.

See some of the incredible works below.

Installation view from “Fantastic Women. Surreal Worlds from Meret Oppenheim to Frida Kahlo.” © Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt, 2020, Photo: Norbert Miguletz.

Claude Cahun, , (ca. 1927). Private Collection. © Claude Cahun

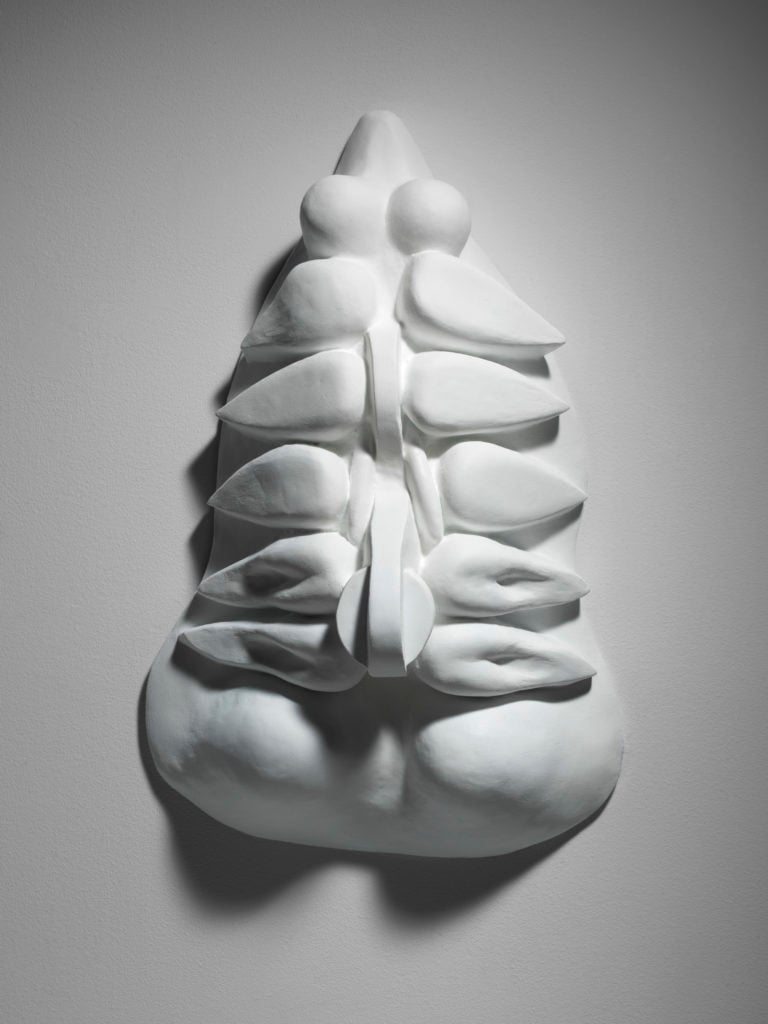

Louise Bourgeois, (1963-64). Collection the Easton

Foundation © The Easton Foundation / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020, Photo: Christopher Burke.

Frida Kahlo, (1940). Collection of Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin, Nickolas Muray Collection of Modern Mexican Art © Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020.

Installation view from “Fantastic Women. Surreal Worlds from Meret Oppenheim to Frida Kahlo.” © Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt, 2020, Photo: Norbert Miguletz.

Kay Sage, (1942). Newark Museum of Art, Bequest of Kay Sage Tanguy, 1964 © Estate of Kay Sage/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020

Bridget Tichenor, , (1956). Private Collection Mexico, © Bridget Tichenor.

Source: Exhibition - news.artnet.com