New York’s latest pop up museum isn’t about ice cream, pizza, or rosé. It’s called Sex Workers’ Pop-Up, and it’s promoting the global campaign to support sex workers’ rights, featuring more than 50 works by 22 artists—17 of whom have backgrounds in sex work.

“Sex work is really misunderstood, misrepresented, and stigmatized, so it was important in this show to have people hear from sex workers directly about their experiences and their demands,” co-curator Daveen Trentman, cofounder of the Soze Agency, told Artnet News. “The message that we want to send with this exhibition is that sex work shouldn’t be criminalized.”

The exhibition has been organized by the Open Society Foundation, a philanthropic grant-making organization, with the assistance of Soze, a creative agency that specializes in creating social impact campaigns—like the New York Civil Liberties Union’s Museum of Broken Windows in 2018.

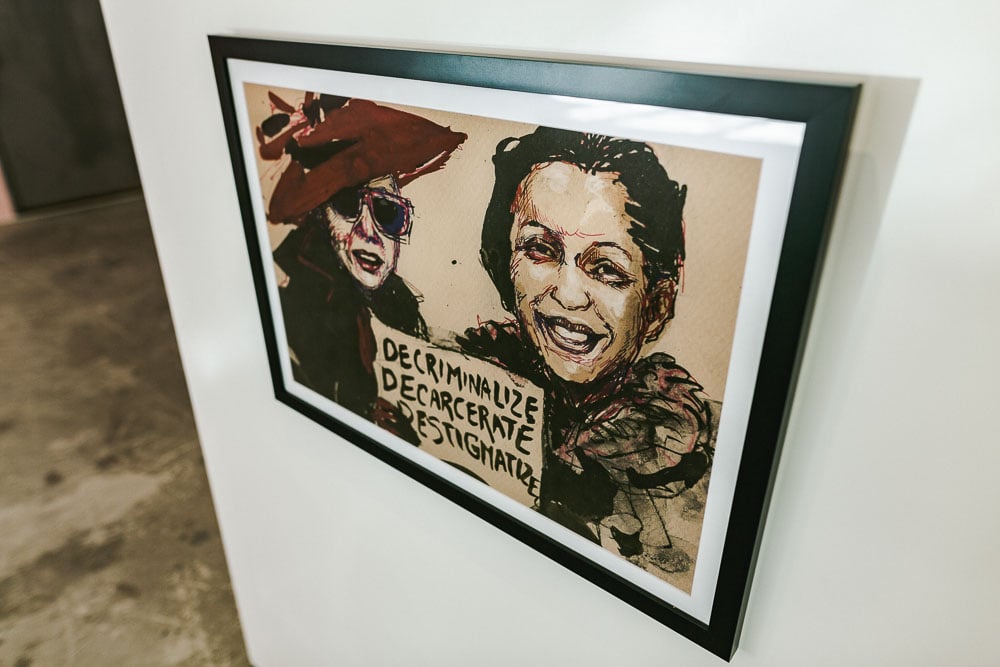

But while that exhibition featured such well-known artists as Dread Scott and Hank Willis Thomas, the museum of sex workers relies almost exclusively on less familiar names. Yes, there’s Venice Biennale veteran Candice Breitz, whose video series featuring accounts from sex workers has been shown widely in Europe, and activist artist Molly Crabapple. (The latter, who has illustrated sex workers’ magazine is presenting drawings made of rallies held by DeCrim NY, an advocacy group working to legalize the sex trade in New York.)

Work by Molly Crabapple at Sex Worker Pop-Up. Photo courtesy of Sex Worker Pop-Up.

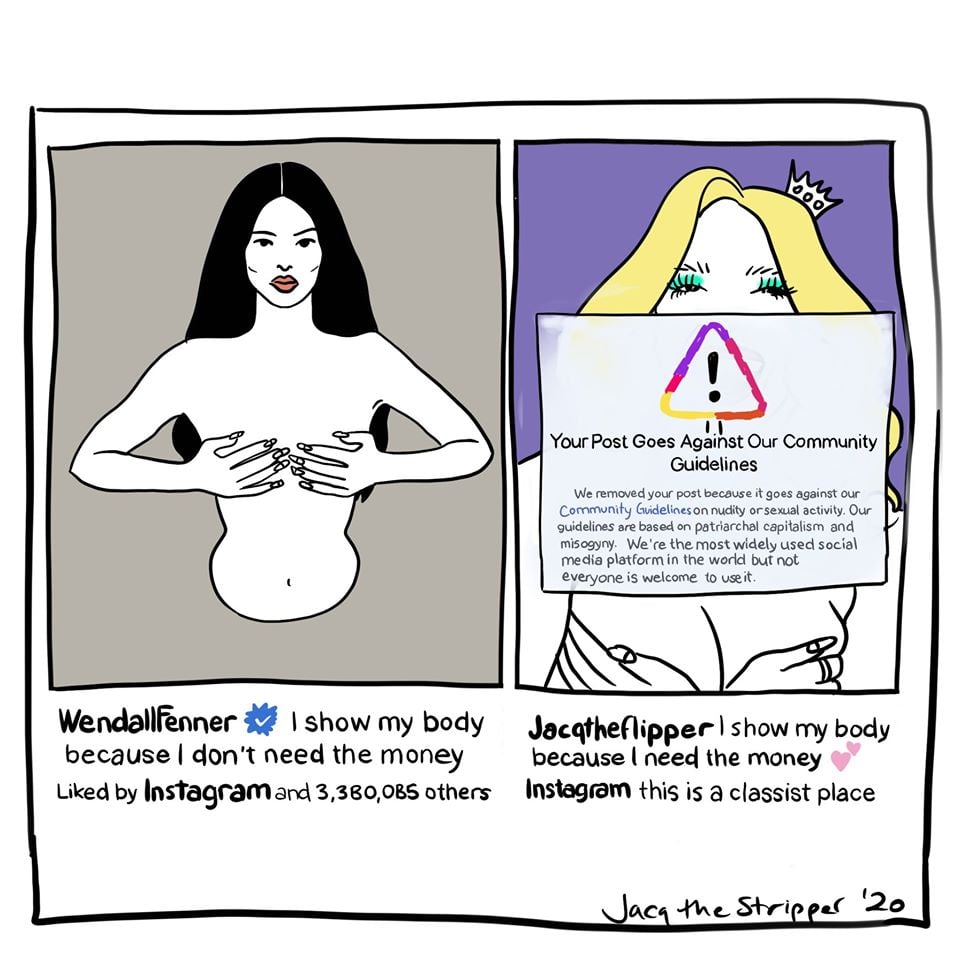

But you’ll also find single panel cartoons by Jacq the Stripper—including , comparing an Instagram post of the artist hugging her bare breasts that was censored by the platform with a one featuring Maurizio Cattelan’s recent topless sculpture of Kendall Jenner, which received a like from Instagram’s official account.

“At the core of this exhibition is authentic storytelling,” said Trentman, who teamed with Alexis Heller, curator of the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art’s recent exhibition “ON OUR BACKS: The Revolutionary Art of Queer Sex Work” to find the right mix of artists for the show. “When we’re talking about policy it’s one thing to debate it, but it’s another to see the human side of it.”

Jacq the Stripper, (2020). Courtesy of the artist.

To illustrate the ways in which black cis women and black trans women alike have historically been over-criminalized and over-policed for sex work, the curators commissioned photographer Kisha Bari to shoot portraits of women in the sex trade. “When you look at these portraits, there is such a range of emotion that was captured,” said Trentman. “They really speak to the resilience that these women have.”

Installation view of Kisha Bari’s portraits of black and brown sex workers at Sex Worker Pop-Up. Photo by Jonna Algarin Mojica courtesy of Sex Worker Pop-Up.

Another highlight is the work of Brazilian photographer Gabriela Leite, who runs the fashion line DASPU, which means “of the whores.” The brand employs sex workers as models on the catwalk, turning runway shows into political activism. The curators printed the black-and-white images of these events on tapestries, hanging them an inch off the wall so that they flutter a little as visitors walk by.

“We wanted to capture the spirit of these fashion shows,” said Trentman. “They are very lively, and they’re about empowerment, self confidence, resilience, and joy.”

A more personal work is Midori’s , a 20-foot-tall interactive textile sculpture that appeared in the Leslie-Lohman show. Visitors are invited to step inside the hemp rope curtain, which is interwoven with garments once used by queer sex workers. They’ve ritualistically retired these once-precious belongings, imbuing the piece with a sense of collective memory.

Midori, , installation view. Photo by Jonna Algarin Mojica courtesy of Sex Worker Pop-Up.

The work on view is thought-provoking, offering an illuminating portrait of a marginalized segment of society forced to operate in the shadows. But Trentman and Heller are savvy curators, offering at least one Instagram-ready moment in the form of an installation of a grid of red umbrellas by Sun Kim.

The umbrellas hang upside-down from the gallery’s skylight, suffusing the space with warm light and offering a striking photo op. But they also have a long history as a symbol of the sex workers’ rights movement. During the Venice Biennale in 2001, the Slovenian artist Tadej Pogačar staged a Prostitute’s Pavilion under a tent, with sex workers marching through the streets of Venice carrying red umbrellas and congregating in the Giardini for the World Congress of Sex Workers.

“The red symbolizes beauty and the umbrella symbolizes strength and protection,” said Trentman.

Sun Kim’s red umbrella installation at Sex Worker Pop-Up. Photo by Jonna Algarin Mojica courtesy of Sex Worker Pop-Up.

The week-long exhibition was planned to coincide with the UN Commission on the Status of Women, which was suspended following the opening meeting due to the coronavirus outbreak. But the organizers still believe that their message will be heard—the Museum of Broken Windows, for instance, saw 10,000 visitors during its week-long run.

“Sex workers are asking for their work to be recognized as work, and to have the same rights that are afforded to other workers,” Sebastian Köhn, director of Open Society’s sexual reproductive health and rights project, told Artnet News. “There’s a demand to be free from exploitation and oppression.”

See more images from the show below.

Sex Worker Pop-Up, installation view. Photo by Jonna Algarin Mojica courtesy of Sex Worker Pop-Up.

Midori, , installation view. Photo by Jonna Algarin Mojica courtesy of Sex Worker Pop-Up.

Empower Condom Police, . Photo by Jonna Algarin Mojica courtesy of Sex Worker Pop-Up.

Pluma Sumaq, , installation view at Sex Worker Pop-Up. Photo by Jonna Algarin Mojica courtesy of Sex Worker Pop-Up.

Installation view of Kisha Bari’s portraits of black and brown sex workers at Sex Worker Pop-Up. Photo by Jonna Algarin Mojica courtesy of Sex Worker Pop-Up.

Installation view of Sex Worker Pop-Up. Photo by Jonna Algarin Mojica courtesy of Sex Worker Pop-Up.

Source: Exhibition - news.artnet.com